Steppenwolf (novel)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Steppenwolf (disambiguation).

| Steppenwolf | |

|---|---|

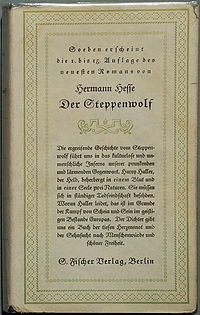

Cover of the original German edition | |

| Author(s) | Hermann Hesse |

| Original title | Der Steppenwolf |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Language | German |

| Genre(s) | Autobiographical, Novel,Existential |

| Publisher | S. Fischer Verlag (Ger) |

| Publication date | 1927 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 237 |

| ISBN | 0-312-27867-5 |

Steppenwolf (orig. German Der Steppenwolf) is the tenth novel by German-Swiss author Hermann Hesse. Originally published in Germany in 1927, it was first translated into English in 1929. Combining autobiographical and psychoanalytic elements, the novel was named after the lonesome wolf of the steppes. The story in large part reflects a profound crisis in Hesse's spiritual world in the 1920s while memorably portraying the protagonist's split between his humanity and his wolf-like aggression and homelessness.[1] The novel became an international success, although Hesse would later assert that the book was largely misunderstood.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Background and publication history @ FIX University

In 1924 Hermann Hesse married singer Ruth Wenger. After several weeks, however, he left Basel, only returning near the end of the year. Upon his return he rented a separate apartment, adding to his isolation. After a short trip to Germany with Wenger, Hesse stopped seeing her almost completely. The resulting feeling of isolation and inability to make lasting contact with the outside world led to increasing despair and thoughts of suicide.

Hesse began writing Steppenwolf in Basel, and finished it in Zürich.[citation needed] In 1926, a precursor to the book, a collection of poems titled The Crisis. From Hermann Hesse's Diary was published. The novel was later released in 1927. The first English edition was published in 1929 by Martin Secker in the United Kingdom and by Henry Holt and Company in the United States. That version was translated by Basil Creighton.

[edit]Plot summary

The book is presented as a manuscript by its protagonist, a middle-aged man named Harry Haller, who leaves it to a chance acquaintance, the nephew of his landlady. The acquaintance adds a short preface of his own and then has the manuscript published. The title of this "real" book-in-the-book is Harry Haller's Records (For Madmen Only).

As it begins, the hero is beset by reflections on his being ill-suited for the world of everyday, regular people, specifically for frivolous bourgeois society. In his aimless wanderings about the city he encounters a person carrying an advertisement for a magic theatre who gives him a small book, Treatise on the Steppenwolf. This treatise, cited in full in the novel's text as Harry reads it, addresses Harry by name and strikes him as describing himself uncannily. It is a discourse of a man who believes himself to be of two natures: one high, the spiritual nature of man; while the other is low, animalistic, a "wolf of the steppes". This man is entangled in an irresolvable struggle, never content with either nature because he cannot see beyond this self-made concept. The pamphlet gives an explanation of the multifaceted and indefinable nature of every man's soul, which Harry is either unable or unwilling to recognize. It also discusses his suicidal intentions, describing him as one of the "suicides"; people who, deep down, knew they would take their own life one day. But to counter that, it hails his potential to be great, to be one of the "Immortals".

The next day Harry meets a former academic friend with whom he had often discussed Oriental mythology, and who invites Harry to his home. While there, Harry is disgusted by the nationalistic mentality of his friend, who inadvertently criticizes a column Harry wrote. In turn, Harry offends the man and his wife by criticizing the wife's picture of Goethe, which Harry feels is too thickly sentimental and insulting to Goethe's true brilliance. This episode confirms to Harry that he is, and will always be, a stranger to his society.

Trying to postpone returning home (where he has planned suicide), Harry walks aimlessly around the town for most of the night, finally stopping to rest at a dance hall where he happens on a young woman, Hermine, who quickly recognizes his desperation. They talk at length; Hermine alternately mocks Harry's self-pity and indulges him in his explanations regarding his view of life, to his astonished relief. Hermine promises a second meeting, and provides Harry with a reason to live (or at least a substantial excuse to continue living) that he eagerly embraces.

During the next few weeks, Hermine introduces Harry to the indulgences of what he calls the "bourgeois". She teaches Harry to dance, introduces him to casual drug use, finds him a lover (Maria), and, more importantly, forces him to accept these as legitimate and worthy aspects of a full life.

[edit]The Magic Theatre

Hermine also introduces Harry to a mysterious saxophonist named Pablo, who appears to be the very opposite of what Harry considers a serious, thoughtful man. After attending a lavish masquerade ball, Pablo brings Harry to his metaphorical "magic theatre," where concerns and notions that plagued his soul disintegrate while he interacts with the ethereal and phantasmal. The Magic Theatre is a place where he experiences the fantasies that exist in his mind. They are described as a long horseshoe-shaped corridor that is a mirror on one side and a great many doors on the other. Then, Harry enters five of these labeled doors, each of which symbolizes a fraction of his life.

[edit]Major characters

- Harry Haller – the protagonist, a middle-aged man

- Pablo – a saxophonist

- Hermine – a young woman Haller meets at a dance

- Maria – Hermine's friend

[edit]Critical analysis

In the preface to the novel's 1960 edition, Hesse wrote that Steppenwolf was "more often and more violently misunderstood" than any of his other books. Hesse felt that his readers focused only on the suffering and despair that are depicted in Harry Haller's life, thereby missing the possibility of transcendence and healing.[2]

Hesse is a master at blurring the distinction between reality and fantasy. In the moment of climax, it's debatable whether Haller actually kills Hermine or whether the "murder" is just another hallucination in the Magic Theater. It is argued that Hesse does not define reality based on what occurs in physical time and space; rather, reality is merely a function of metaphysical cause and effect.[citation needed] What matters is not whether the murder actually occurred, but rather that at that moment it was Haller's intention to kill Hermine. In that sense, Haller's various states of mind are more significant than his actions.

It is also notable that the very existence of Hermine in the novel is never confirmed; the manuscript left in Harry Haller's room reflects a story that completely revolves around his personal experiences. In fact when Harry asks Hermine what her name is, she turns the question around. When he is challenged to guess her name, he tells her that she reminds him of a childhood friend named Hermann, and therefore he concludes, her name must be Hermine. Metaphorically, Harry creates Hermine as if a fragment of his own soul has broken off to form a female counterpart.

[edit]Critical reception

From the very beginning, reception was harsh[citation needed]. American novelist Jack Kerouacdismissed it in Big Sur (1962) and it has had a long history of mixed critical reception and opinion at large[citation needed]. Already upset with Hesse's novel Siddhartha, political activists and patriots railed against him, and against the book, seeing an opportunity to discredit Hesse[citation needed]. Even close friends and longtime readers criticized the novel for its perceived lack of morality in its open depiction of sex and drug use, a criticism that indeed remained the primary rebuff of the novel for many years.[3] However as society changed and formerly taboo topics such as sex and drugs became more openly discussed, critics[which?] came to attack the book for other reasons; mainly that it was too pessimistic, and that it was a journey in the footsteps of a psychotic and showed humanity through his warped and unstable viewpoint, a fact that Hesse did not dispute, although he did respond to critics by noting the novel ends on a theme of new hope[citation needed].

Popular interest in the novel was renewed in the 1960s, primarily because it was seen as a counterculture book and because of its depiction of free love and explicit drug usage. It was also introduced in many new colleges for study and interest in the book and in Hermann Hesse was feted in America for more than a decade afterwards.[citation needed]

[edit]"Treatise on the Steppenwolf"

The "Treatise on the Steppenwolf" is a booklet given to Harry Haller which describes himself. It is a literary mirror and, from the outset, describes what Harry had not learned, namely "to find contentment in himself and his own life." The cause of his discontent was the perceived dualistic nature of a human and a wolf within Harry. The treatise describes, as earmarks of his life, a threefold manifestation of his discontent: one, isolation from others, two, suicidal tendencies, and three, relation to the bourgeois. Harry isolates himself from others socially and professionally, frequently resists the temptation to take his life, and experiences feelings of benevolence and malevolence for bourgeois notions. The booklet predicts Harry may come to terms with his state in the dawning light of humor.

[edit]References in popular culture

Hesse's 1928 short story "Harry, the Steppenwolf" forms a companion piece to the novel. It is about a wolf named Harry who is kept in a zoo, and who entertains crowds by destroying images of German cultural icons like Goethe and Mozart.

The name Steppenwolf has become notable in popular culture for various organizations and establishments. In 1967, the band Steppenwolf, headed by German-born singer John Kay, took their name from the novel. The Belgian band DAAU (die Anarchistische Abendunterhaltung) is named after one of the advertising slogans of the novel's magical theatre. The innovative Magic Theatre Company, founded in 1967 in Berkeley and which later became resident in San Francisco, takes its name from the "Magic Theatre" of the novel, and the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, founded in 1974 by actors Terry Kinney, Jeff Perry, and Gary Sinise, took its name from the novel. The lengthy track "Steppenwolf" appears on English rock band Hawkwind's album Astounding Sounds, Amazing Music and is directly inspired by the novel, including references to the magic theatre and the dual nature of the wolfman-manwolf (lutocost). Robert Calvert had initially written and performed the lyrics on 'Distances Between Us' by Adrian Wagner in 1974. The song also appears on later, live Hawkwind CD's and DVDs.

The second verse of the Simon and Garfunkel song "The Sound of Silence" bears an uncanny resemblance to an early scene in the novel, where the protagonist walks the streets alone; the description in the song echoes details in the novel, including coming upon a brightly lit sign.[citation needed]

In San Jose, Costa Rica, there is a bar called "El Lobo Estepario."

Modest Mouse made a song called "Custom Concerns" which has references to Steppenwolf.

[edit]Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

The novel was adapted into a film of the same name in 1974. Starring Max von Sydow and Dominique Sanda, it was directed by Fred Haines.

[edit]See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]References

- Cornils, Ingo and Osman Durrani. 2005. Hermann Hesse Today. University of London Institute of Germanic Studies. ISBN 90-420-1606-X.

- Freedman, Ralph. 1978. Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis: A Biography. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-41981-2. OCLC 4076225.

- Halkin, Ariela. 1995. The Enemy Reviewed: German Popular Literature Through British Eyes Between the Two World Wars. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95101-4.

- Mileck, Joseph. 1981. Hermann Hesse: Life and Art. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04152-6.

- Poplawski, Paul. 2003. Encyclopedia of Literary Modernism. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-01657-8.

- Ziolkowski, Theodore. 1969. Foreword of The Glass Bead Game. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-1246-X.

[edit]External links

- Steppenwolf the Genius of Suffering by Hassan M. Malik

- Steppenwolf at the Internet Movie Database

| ||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment